Screenshot of Zoom recording from Dec. 11 ZBA meeting

Screenshot of Zoom recording from Dec. 11 ZBA meeting

By Marissa Marvelli

On Thursday, December 11, nearly six months after its last deliberation, the five-member Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) unanimously reversed its June 12 decision regarding the historic Sleight-Tappen/DAR House windows. Over three hours, the board, led by chair Anthony Tampone Jr., carefully applied the preservation review criteria that guide the Historic Landmarks Preservation Commission (HLPC) in evaluating changes to landmark-designated buildings and districts. Members repeatedly cited the extensive record compiled since 2021, when the Wiltwyck Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) was first notified that exterior work on the building required review. Assistant Corporation Counsel Matt Jankowski aided the board in drafting a detailed decision typical of the HLPC.

During deliberations, Tampone and other members acknowledged that the board had been misled back in June about the proposed replacement windows. Contrary to the DAR’s prior assertions, the windows are not “exact replicas” of the existing historic windows; they are generic replacements. Tampone explained that he personally confirmed this by contacting a Marvin window representative, who said that the measurements that were taken were only of the overall openings, and not any of the other window details. The board engaged in a lengthy discussion about the special qualities of historic windows, how they differ from modern replacements, and how the cumulative effect of 32 rigidly square contemporary windows would diminish the architectural integrity of one of the Stockade’s significant historic buildings. Members also noted that, in a 2023 affidavit, the DAR itself admitted that restoring the historic windows would have been more cost-effective. Board members struggled to understand why they did not go that route. The costs associated with replacements have undoubtedly increased since the chapter engaged in a protracted legal dispute.

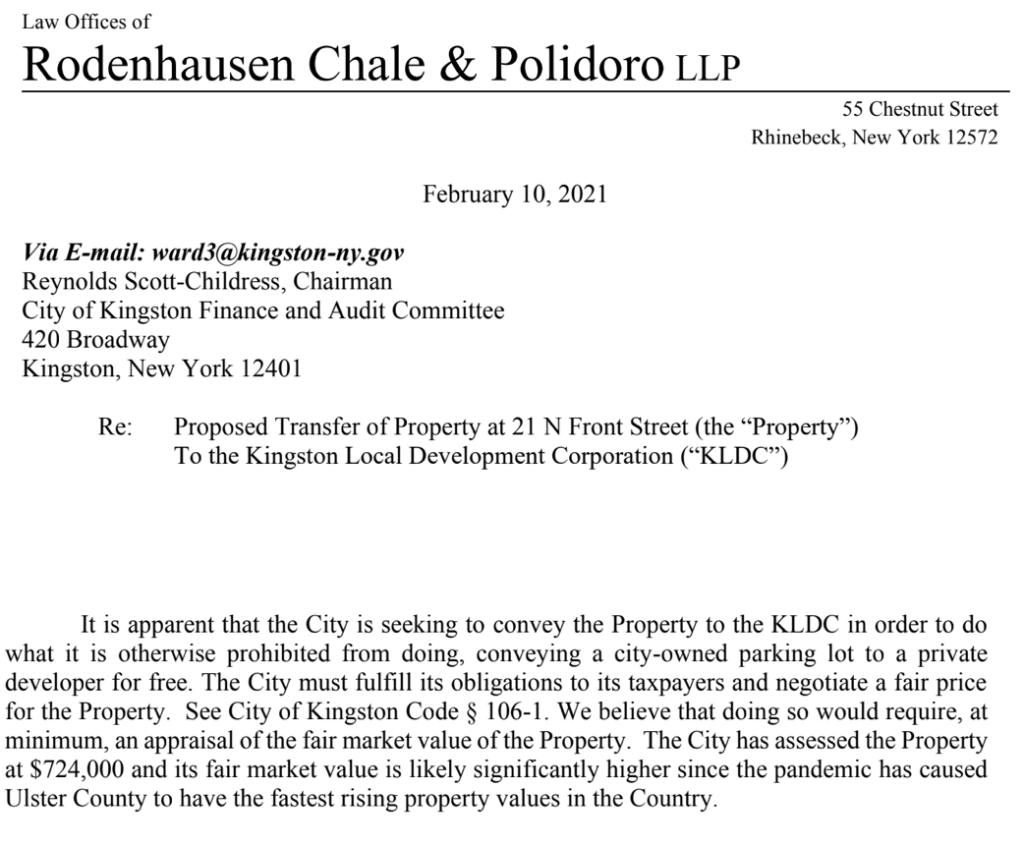

The DAR’s attorney, James Bacon, a sitting judge in New Paltz, was the sole representative of the applicant present. The board permitted him to testify before their deliberation began. Much of his case consisted of recycled arguments already refuted or dismissed by both the ZBA and HLPC. Most notably, Bacon again asserted—incorrectly—that only federal recognition of a building’s individual significance permits regulatory control over exterior features. The City of Kingston, a certified local government with a historic preservation ordinance, has the authority to carry out municipal responsibilities for its historic preservation program. It is largely carried out by its trained and qualified commission, the HLPC, which reviews and approves exterior changes to its locally designated landmarks and in local historic districts. The DAR House is both an individually designated landmark (since 1969) and a contributing building in the Stockade Historic District. The building’s—or district’s—listing on the National Register of Historic Places is irrelevant to the City’s authority in this matter.

Generously interpreting an old brochure of preservation guidelines, Bacon repeated the DAR’s justification for failing to seek HLPC approval before expending $65,000 on Marvin replacement windows in March 2022, the same month Kingston Planning Director Suzanne Cahill contacted the chapter for a second time to confirm that exterior work required review. The DAR has previously admitted that it did not consult the City of Kingston’s administrative code before proceeding.

The credibility of the DAR’s case was further undermined when Chair Tampone questioned Bacon’s submission of what was plainly an AI-generated query summary as an exhibit for the record. Under questioning, Bacon explained that he was unaware the document was AI-generated and that it had come from Kaaren Davis, the chapter’s treasurer, and originated with her son, Harley Davis, whom Bacon stated is also the contractor for the window replacement project. Bacon agreed it should be removed from the record, adding that he would not have accepted such a submission in his own court.

What was made abundantly obvious last night is the urgent need to address the ambiguity in Kingston’s administrative code. A questionable interpretation by the Corporation Counsel forced the ZBA to serve as a de facto landmarks commission without the requisite training, expertise, or experience. While the ZBA members should be applauded for their thoughtful deliberation last night, they should never have been put in the position of re-deciding the HLPC’s certificate of appropriateness decision rather than its subsequent hardship denial. A code amendment is now being prepared for Common Council adoption in the new year.

What’s Next?

The unanimous ZBA decision is not the end of this advocacy effort. The DAR will likely return to court for judicial relief, where a single judge, Honorable Sharon Graff, could overrule the hundreds of hours expended by city staff, volunteers on the HLPC and ZBA, and advocates to review, uphold, and defend Kingston’s preservation law. Graff is more likely to side with the DAR—and possibly award them financial compensation—in the absence of a response from City of Kingston’s Corporation Counsel Barbara Graves-Poller, who, to date, has not publicly acknowledged the DAR’s article 78 petition filed in State Supreme Court on July 25, despite the frivolous nature of the suit.

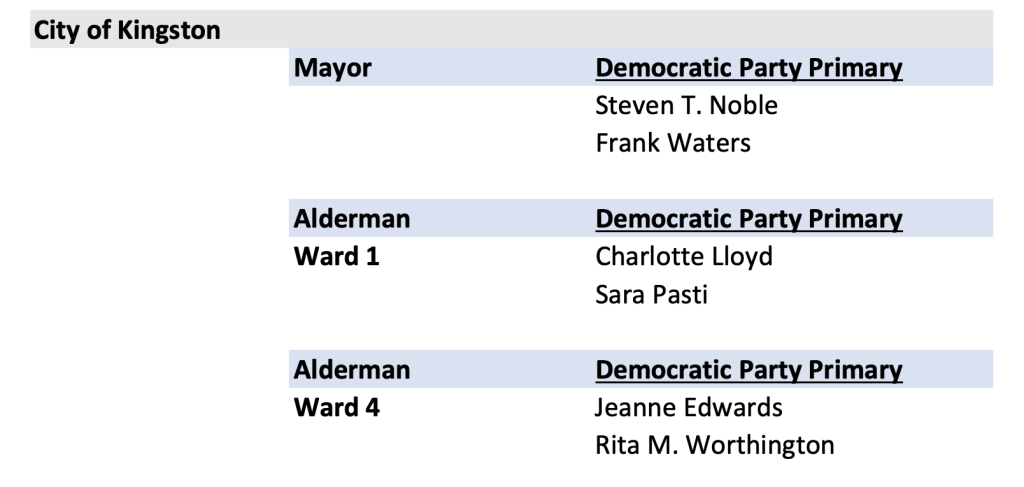

Civic engagement is not episodic; it’s a daily practice. Meaningful change, whether in historic preservation, zoning reform, affordable housing, or charter reform, is a long game that depends on sustained public participation. Almost without exception, high-stakes conflicts like the DAR House case expose the weaknesses in our democracy. Here, that weakness is Kingston’s strong-mayor form of government, codified in our three-decades-old “city manager” charter. Just weeks after receiving a controversial $30,000 salary increase, Graves-Poller continues to operate within a system in which her office serves at the mayor’s pleasure. With Mayor Steve Noble up for re-election in 2027, this structure inherently discourages independent representation of the Common Council when disagreements between the two branches arise. The DAR House case is simply the latest instance in which this flaw has been exposed.

Call to Action:

- Demand a strong legal defense. Write to Mayor Steve Noble and urge him to direct the Corporation Counsel’s office to defend the hard work of the HLPC, ZBA, and city staff on the DAR matter in court. These volunteer boards and public servants followed the law and deserve the city’s full backing in court. Letters can be emailed to SN****@*********ny.gov or mailed to Office of the Mayor, 420 Broadway, Kingston, NY 12401.

- Show up and speak out. Use the public comment period at monthly Common Council meetings to urge the Council to have its own staff, specifically, an independent counsel and independent clerk. This independence is essential for good governance and for the Council to effectively carry out its responsibilities, especially as it prepares to oversee the city charter review process in 2026-2027, a process the Mayor recently declined to support. The next council meeting is on Wednesday, December 17. The following hearing will be Tuesday, January 6, when four new council members, including myself, will be sworn in.

Background Reading

“Preserving Our History and the Laws That Protect It” KingstonCitizens.org, Aug. 20, 2025

“Local Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution Battling Against Kingston’s Historic Preservation Law” KingstonCitizens.org, July 3, 2025

“Kingston slaps stone house with stop-work order over window renovations” by Brian Hubert, Daily Freeman, July 25, 2025.

Correction (December 15, 2025): This post previously misstated the year of the Mayoral election. It is in 2027 and has been corrected here.